You can't pick produce by zooming.

I have been an immigrant rights activist since 2010, organizing protests against ICE detention centers, helping young people obtain DACA, and working to provide housing, legal, and financial assistance to undocumented immigrants. I do this work to serve and energize the community to which I belong. Growing up as an undocumented immigrant (I received DACA in 2013), I know all too well the struggle of needing support but having to hide behind a system that does not recognize you while relying on your work.

This summer, as pandemics and wildfires raged in my part of California, I was devastated to see the suffering in my community. However, I had an opportunity to become more involved in my own activism. The catalyst for this was a video.

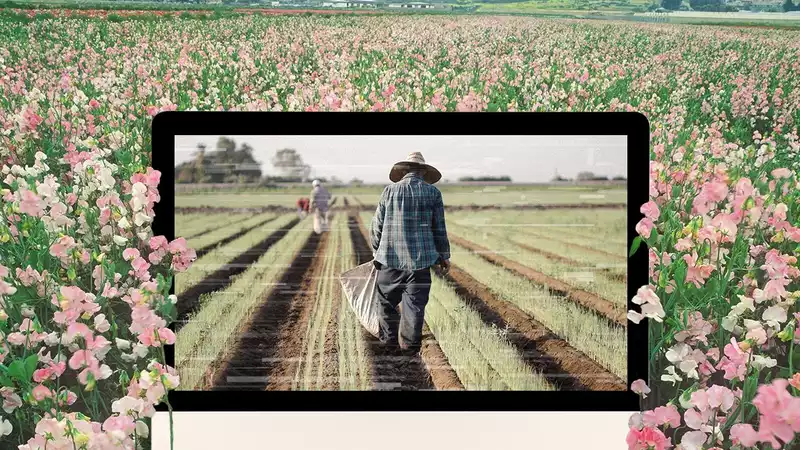

One day, my sister showed me a social media post of a farm worker harvesting grapes in a vineyard near Salinas, California. The area is often referred to as "America's Salad Bowl" because of its thriving vegetable and fruit crops. Behind them, a blazing wildfire was billowing huge plumes of smoke. All they had with them was a bandana for protection.

But they continued to work as if almost nothing had happened. Most farmworkers are informal (open in new tab), working in low-paying jobs with no benefits, and cannot afford to take a single day off. These informal workers receive neither stimulus checks nor unemployment benefits. Despite deadly pandemics and climate catastrophes, we rely on them to come to work every day and risk their own lives to provide for us. They, too, are essential workers for America. Yet we have failed to show up for them.

Looking at this post was like looking in a mirror. When I was 15 years old, I worked with my parents and sister picking grapes on various farms in Northern California, often for up to nine hours a day, and it was not uncommon for me to finish my shift dehydrated with sore muscles from all the physical exertion required to separate the fruit from the vines. They often worked in scorching heat. Gloves, hats, bandanas to protect him from the pesticide dust, and even clippers for work. The money earned was used by the parents to provide for the family's needs (food, rent, clothing, etc.).

When I saw the video, my heart ached. I spent all day ranting to my family about it. At one point, my sister said, "We're still talking about it. I'm still talking about it. The video evoked so much emotion in me that I wanted to do more than just share it on social media. I wanted to do something to turn that anger into positive change.

Over the next few days, I went out to several sites and asked the workers, "How can I help you?" I asked. I had already thought of masks to protect them from the smoke and coronavirus, but I thought maybe they might want some money or tools like gloves.

Their response was quite different. They wanted backpacks and school supplies for their children. When asked what they could do to protect themselves, they put their own health aside and prioritized their children's education. Even when they had the chance to improve their own situation, they again chose to put the lives of others before their own.

I set up a GoFundMe (opens in new tab) page in August and set the goal at $5,000. Within minutes, donations poured in. So far, $200,000 has been raised, with another $300,000 coming to Venmo. I was completely shocked by the outpouring of support and generosity, especially at a time when people's finances may have been shaken by the pandemic.

Half of the funds go to masks and half to educational tools such as basic supplies and internet hotspots. In the beginning, I simply showed up at the fields with my partner and family to distribute supplies. On the first day, workers ran to their backpacks. It was as if instead of folders and pencils, they had expensive laptops in them. So much so that they needed the goods inside. I was so moved that I cried by the side of the field.

I decided to organize a massive distribution throughout Northern California. Each time, I handed out thousands of backpacks filled with notebooks, folders, markers, rulers, and pencils. We also signed up for T-Mobile Internet hotspots. Many students are still distance learning, but a huge number of them do not have access to the Internet. [So far, we have already given out 8,000 masks and 12,000 backpacks, and 110 families have signed up for hotspots. We intend to keep going until we run out of funds. Donations continue to come in. Ultimately, we want to set up a place where people can come at their convenience and get these supplies and any other resources they might need.

Although the pandemic has thrown a wrench in my professional life, I think it has been a blessing in disguise. In addition to my work as an activist, I run an events company, and COVID caused many of my events to be cancelled or postponed, freeing up some of my time. Financially it was tough, but it allowed me to focus on giving back to the community. And this activity is my calling.

Because my family was undocumented, I was always told growing up to stay in the shade: to blend in, to stay out of trouble, to not be different. becoming a DACA recipient has made me an activist, organizing for those who have no voice or power to make change. I started organizing for them. I always tell Dreamers (those affected by DACA) that they must speak up for their parents and friends who still live in fear. If not us, who. If not now, when?" Farmworkers are essential. It is time to stand up and serve them, just as they have served us time and time again.'

.

Comments