On being a black woman, a mother, and a breast cancer survivor

Approximately 1 in 8 American women (open in new tab) will be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetime. Each Monday during Breast Cancer Awareness Month, we will document one Black mother and survivor's journey through the uncertainty of breast cancer in these uncertain times.

Over the past two years, I have lost two friends, also Black women, to metastatic breast cancer (opens in new tab) (MBC) Both were young, talented, and successful. The diagnosis came like a thief in the middle of the night, trying to take away everything I had come to believe about what it means to plan for the future. I was eagerly awaiting the results of my own breast biopsy this summer when I learned that a friend had died of MBC that had spread to her bones. The weight of her passing, combined with the gravity of waiting again for the tests that would reveal my fate, influenced my recent choices regarding my health journey.

The death of a friend, a sister in the struggle, is never far from my daily thoughts. A cough makes me think of a more devastating disease, a muscle ache after a workout makes me feel gloomy, a coughing spell makes me think of a more devastating disease, a coughing spell makes me think of a more devastating disease. Being a cancer survivor brings on an unspeakable heaviness. It colors every decision in a way that can only be described as life-changing.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), black women die of breast cancer (open in new tab) at a higher rate than white women. Furthermore, black women are diagnosed with breast cancer later than white women. As this Covid-19 pandemic (in which Blacks and Latinos are dying disproportionately (open new tab)) continues to show, the disparity between communities of color and white communities, especially wealthier ones, is alarming when it comes to overall mortality rates.

Every decision I make regarding breast health is informed by my identity as a Black woman, as a survivor, and as a friend who watches her beautiful warriors in their 30s and 40s become faded memories. I am acutely aware that I must be my own advocate in the struggle to survive. Statistics (opens in new tab) show that the treatment patients in poor black communities receive in the current health care system is deplorable. Residents of these communities tend to live in food deserts and suffer from chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and asthma. This is a public health crisis, and if not addressed, communities of color will continue to lose vital lives that will never be replaced.

It is possible that I was a victim of a racist healthcare system. I was diagnosed with stage II invasive ductal breast cancer in 2014. I believe I should have been diagnosed at Stage I, but my health care provider at the time did not order a biopsy. It wasn't until a year after I moved to a new state and changed doctors that the tumor became much larger and was determined to be malignant after a biopsy. I do not know, and will never know, whether my age or race was a factor in the first doctor's cavalier response to my concerns.

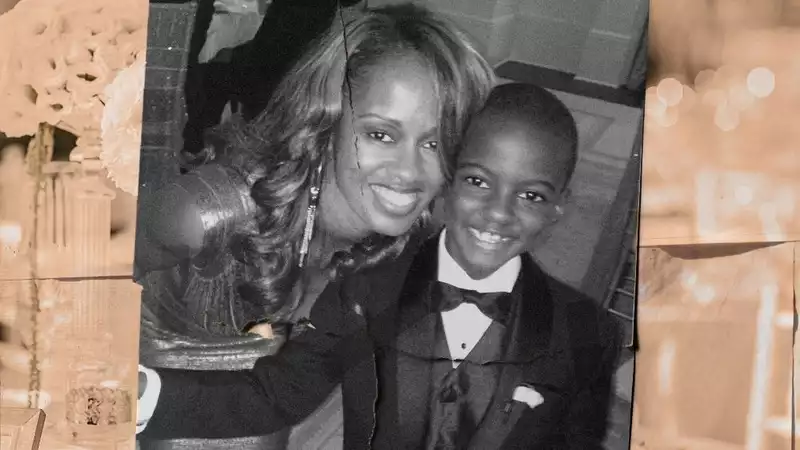

The greatest gift I have received in life is motherhood; being the mother of a teenage son is also a major determinant of my breast health; the only thing I asked for when I battled cancer six years ago was a soccer mom carpooling, practicing sports, and frustrating my smelly sons who eat all the groceries I wanted them to have the privilege of living long enough to let me. To be asked to guide them through the college entrance exams, to be able to wipe away the tears of my son's first broken heart. Every milestone he reaches, every accomplishment he achieves, every questionable teenage choice he makes, I want to be there for all of it. My daily joys are my son's sweaty hugs, his naughty smiles, his sarcastic wit. Nothing in my son's life, or my own, is taken for granted. Knowing what anxiety and despair a tough diagnosis can bring, I cannot afford to take life or time lightly.

Thanks to Covid-19, I had over two months to make a decision on how to deal with the diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia. I intend to proceed with a partial mastectomy to remove the breast tissue in the area where the June mammogram and subsequent biopsy revealed suspicious calcifications. Enduring a bilateral mastectomy (with a grueling recovery process) in the stress, isolation, and duress of this covid 19-filled world is not something I am mentally prepared to deal with. Having a partial mastectomy allows me to breathe a little easier. The breast surgeon and his staff are kind, thorough, and cooperative. I feel safe in their hands.

On the day of my surgery, I enter the hospital alone, am sedated alone, and wake up to the face of a nurse whose name I do not know. This is not how I would write a script, but I am not going to revel in my solitude. Because I believe that I will be embraced by angels whose destiny is different from mine.

.

Comments