Educating Women and Girls is Essential for Climate Justice

One morning, when I was only a few years old, I was gone from home. My parents looked everywhere for me. Eventually I was found sitting in a classroom at a nearby preschool. The next day the same thing happened. My father asked the teacher what to do because I was too young to enroll in preschool but would throw a tantrum if taken out of the classroom. The teacher replied that it was illegal for my father to pay to educate a minor child, but agreed that I could stay free. So I went to school every morning and ended up enrolling a year earlier than I should have. [I was very fortunate that my parents advocated for my education, especially as a girl, and worked hard to ensure that I could afford schooling, even during my poor years. My mother stressed that I would have no future unless I studied, acquired expertise and skills, and was able to earn an income for myself. For my mother and for me, it is essential for women to be financially independent, regardless of whether they are married or not.

My father insisted the same. My father has done his best to put himself and his siblings through school. Like my mother, he saw how the lack of education limited the potential of children, especially girls. He wanted to empower me and my two sisters to grow up to be strong women who knew their rights and could claim them and achieve a better position in society. Like me, he earned his degree from MUBS (open in new tab).

My parents' passion for education extends not only to their five children, but also to their three cousins. The cousins pay for their schooling and are just as concerned about their education and future prospects as we are. My sister Claire is in college to become a veterinarian, and my sister Joan graduated from high school in 2019 and received government aid for college. Paul Christian is entering his last two years of middle school and Trevor is in sixth grade.

Girls' education is not a high-tech or new idea; it has been a pillar of global development policy for decades. In fact, you have probably heard many leaders, both male and female, testify to how important it is for girls to attend classrooms at the same level as boys. In Uganda, equality between girls and boys in primary education has been largely achieved. That is an achievement, of course, but still thousands of girls and boys are not in the classroom, and many girls, like my mother's generation and some of my relatives today, leave school before completing secondary education. This means that relatively few Ugandan girls go on to university. When I was a student at MUBS, there were many young women in my class. Even if there were many women in college, there are many more who are not.

Of course, I have an interest in educating boys, and with two brothers, I must do so. However, throughout sub-Saharan Africa, at least 33 million girls who should be able to attend primary and secondary education (equivalent to primary and secondary school and the first two years of high school) are not attending. More than 50 million girls in the region are missing out on upper secondary school education (equivalent to the last two years of high school in the United States and the sixth grade in the United Kingdom). Worldwide, more than 130 million girls are out of school and should be able to attend. How many of these young women, if given the chance, would become teachers, lawyers, doctors, NGO staff, parliamentarians, or climate scientists?

I think of it this way. Girls and women make up more than half of the world's population. If we are to successfully address the climate crisis, women need to be present where decisions affecting the climate are made, which is almost every decision nowadays. Educating girls can get them into those rooms and expand the number of decision makers and possible solutions and approaches.

At present, neither access nor the positive outcomes that would result are being realized fast enough. This reality is a result of the disempowerment of girls. It is certain that tens of millions of girls, and countless others throughout Africa, want to study through high school and university. But many other girls question their prospects and abilities: "My mother couldn't even get this far in school, so why do I think I can make it to that level or even beyond?" they tell themselves. Why do I keep going? [I could move from the village to Kampala and work as a maid for a wealthy family. [The young women we passed while we were holding placards at the strike probably live that way. What are these women doing, you might ask yourself with a mixture of curiosity and bewilderment. But there is no time to think further. She is probably in a hurry, looking for the fastest way to secure the daily necessities her employer has asked for. So she hops on the matatu (public minibus) and returns to preparing dinner, washing the floors, and cleaning the family's clothes. To be honest, I don't see her paying any attention to us at all.

How can someone like her be a climate change activist, let alone a young woman in the village? Realistically, she probably only has a flip phone. That would make access to the Internet difficult and expensive. By the time she turned 20, she would probably be looking for another job. Her employer would probably fire her, worried that her husband would look at the young woman in a sexual way. This happens all the time. When this happens, she will struggle to find a new source of income and stability.

It may not be the worst fate, but is that really all we want for these women? To me, these are "survival" lives. Would these women have chosen these futures if other paths had been open to them, such as finishing middle school, earning a college degree, getting a job and becoming financially independent, or becoming an activist?

It is a depressing reality that the covid epidemic is exacerbating the situation I have described in the same regions of the globe where the climate crisis has become a daily emergency. The effects of covid and climate change are putting increasing pressure on household budgets throughout Africa, Latin America, and Asia. School fees, especially for girls, have become a luxury that must be separated from household finances, as Hilda Nakabwe did. Millions of girls and many boys may never return to school once it fully reopens. We may never know for sure how many children and adolescents have been affected, and we may never be able to total all the costs of the pandemic to them, to society, and to the climate.

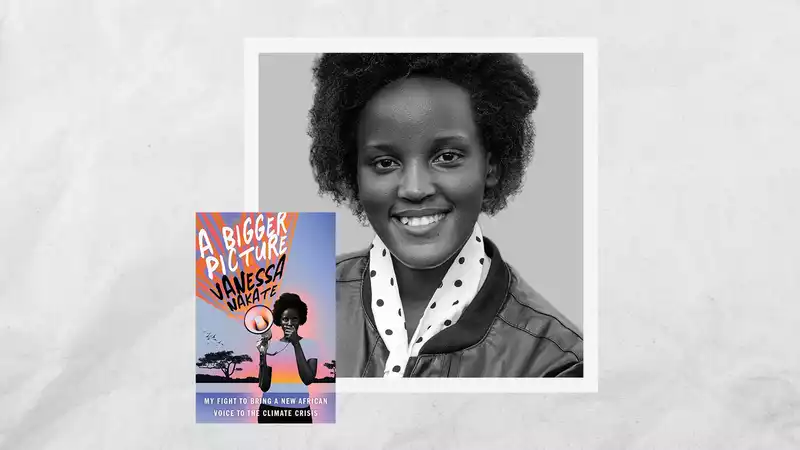

Excerpted from A BIGGER PICTURE: My Fight to Bring a New African Voice to the Climate Crisis by Vanessa Nakate. Copyright © 2021 by Vanessa Nakate. Reprinted with permission of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved.

.

Comments