Reasons for choosing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine at 32 weeks gestation

Tolwarase Ajayi, M.D., is a pediatrician, palliative physician, and clinical researcher in his late 30s living in San Diego, California. On January 9, at 32 weeks gestation, Dr. Ajayi received the COVID-19 vaccine. This despite her initial concerns about the lack of clinical trials with pregnant women and the natural distrust that many in the black community have of the health care system. Here, in her own words, she tells Marie Claire how she came to her decision and why she continues to advocate for underrepresented populations to be included in research studies.

The vaccine became available [at both hospitals where I work] in late December. Early in my pregnancy, I planned to wait to get the vaccine until after the birth, but I decided to take my own medical advice because my job exposes me to radiation. I consulted my OB/GYN. You are high risk, you should get it. You have always done well with vaccines and have never had any problems. She recommended that I wait until my clinical schedule was a little more open to get the vaccine. I worked all through Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year's, so I didn't get any time off until I was 32 weeks pregnant.

My main concern was that pregnant women were not enrolled in the vaccine clinical trial. Therefore, as with any patient population, we did not know conclusively about the effects on the mother and the fetus. Regardless of whether pregnant women were enrolled in clinical trials or not, minorities were disproportionately underrepresented in clinical trials (open in new tab). It is a vicious cycle. We don't participate because of what happened to us in the past, but because we don't participate, we don't get the data we need to feel comfortable.

I also have pregnancy-induced thrombocytopenia (open in new tab). One of the rare side effects of the vaccine is an immune response that can induce thrombocytopenia and further reduce my [platelet] count. This was one of the pieces of information that really, really freaked me out. I consulted with a hematologist friend and an OB/GYN friend, and they told me, "There is that risk with any vaccine. In fact, the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine has a higher risk than the COVID vaccine. So once I had that information, I was satisfied. My husband said, "Just do what makes sense to you, I will support you either way." My sisters and my mother were very nervous for me. They actually kept quiet about my decision. They saw (my post) on Twitter. My mother is very persuasive, but I was just going to do it and then we would discuss it afterwards.

I got the vaccine at Scripps Green Hospital here in La Jolla where I work. There was a small group of us black pregnant women who were talking about getting vaccinated at the same time. One of them said, "I'll wait." The other said, "I'm past the early stages of pregnancy. I'll do it."

I had the choice of either the Modena or Pfizer vaccine. It really wasn't painful. It was less painful than a flu shot and much less painful than a tetanus shot. I am pregnant, and no one who was visibly pregnant had been vaccinated yet. I asked the nurse and she was like, "Yeah, you're the first pregnant woman I'm vaccinating." When you get vaccinated, try to move your arm a little bit so it doesn't hurt. So I did. After the shot, I was kept waiting. Normally I would have to wait 15 minutes after that, but she made me wait an extra 5 minutes to make sure I wasn't responding to it. I then went in for my clinical shift at work.

My arm was a little sore, but by the end of the day the pain was gone. What I felt more was an increase in fatigue. The next morning, I woke up tired and had a small headache. Maybe it was dehydration, maybe it was from being in the hospital for nine days straight. Before I went to work the next day, my blood pressure was a little elevated, but by the time I got home from work, it had returned to normal. The headache was also gone. I didn't take any Tylenol either.

The second vaccine is scheduled for Saturday, January 30.

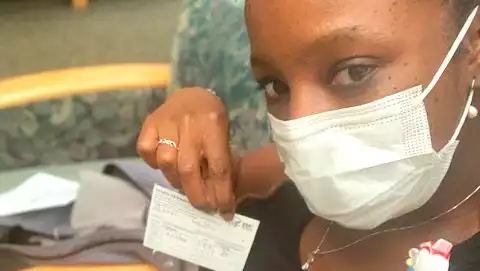

I decided to tweet about getting the vaccine. It was definitely spur of the moment, but I figured if I was going to do this, and tell my patients to do this, I would go public and share what it was like to go on that journey. I was sitting in my chair, observing, and people walking by were looking at me. It was not professional. I was one of those black women who was apprehensive about getting the vaccine, but I figured it was better than getting sick, so I'm doing this. [As an adult palliative care physician, I see many Hispanic and black patients in the ICU. It is tragic. This community is very family oriented. Being with family is a big part of our culture, and if you are COVID positive, you are not allowed to visit, so you can't even come to visit. I guess I was thinking about that too [when I decided to vaccinate].

After I was vaccinated, I participated in several research trials and reported how I felt. This is part of my work with the Scripps Research Institute. I have an app called PowerMom (opens in new tab) and its purpose is to gather information about what happens to women during pregnancy. This is because, in general, pregnant women are left out of clinical research. As a result, we don't know much about our bodies and what is happening to us. Therefore, Power Moms aims to get all of that information and give it back to women so they understand that they are not alone. I will also be collecting data on pregnant women who have been vaccinated and tracking their symptoms to create a large database, which will be used by the COVM to track their symptoms, and to help them understand that they are not alone. The (app) relaunch will focus on COVID, vaccines, and symptoms, and will truly target under-represented minorities.

It would be nice if the people doing the research were more like those we are trying to recruit and create more funding opportunities. I would also like to see a closer look at what barriers exist in getting black women into medicine, clinical trials, and research. Things that generally make being a black woman difficult are not taken into consideration. I would like to see the government take a more proactive approach. Honestly, that goes for any disproportionate group.

I don't blame pregnant black women for hesitating to vaccinate. What we do have is solid information (opens in new tab) that if you are black, if you are Hispanic, you are at a higher risk of dying [from COVID-19], you are at a higher risk of being in the ICU, you are at a higher risk of being in the ICU, you are at a higher risk of being in the ICU, you are at a higher risk of being in the ICU, you are at a higher risk of being in the ICU, you are at a higher risk of being in the ICU. We know that this disease is worse than the vaccine. We also know that pregnant women are worse off with COVID-19 because we are a high risk population. So please consider the fact that you are in the minority and are pregnant. You would not want to take such a chance. The known facts of the disease outweigh the uncertainties about the vaccine.

If you are pregnant, the CDC advisory committee recommends that you consult your physician about the COVID-19 vaccine. For more information on the COVID-19 vaccine, including safety and dosing protocols, click here (opens in a new tab).

.

Comments