Period. End of Sentencing. Encouraging the Restructuring of the Menstrual Equality Movement

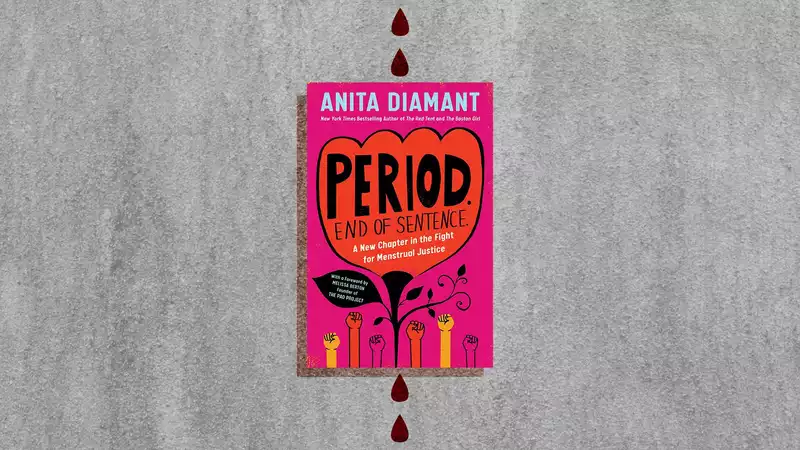

When "The Red Tent" (opens in new tab) - Anita Diamant's fictional chronicle of the biblical life of Jacob and Leah's daughter Dina - was published in 1997, it attracted a devoted following and became the talk of feminist book clubs and religious scholars. It was so well-loved that it was turned into a television miniseries in 2014. In many ways, the ancient camaraderie and community that Diamant revealed, and all the connections brought about by menstruation, were early precursors to today's modern movement for menstrual equality (opens in new tab). And now, nearly 25 years later, she has released its encore: Period: End of Sentence: A New Chapter in the Fight for Menstrual Justice (opens in new tab) (available today).

The book was inspired by the 2019 Academy Award-winning short documentary film of the same name (opens in new tab), produced and created through a school club (opens in new tab) formed by a group of Los Angeles students and educators. After the film venture morphed into a global education and advocacy initiative called "The Pad Project" (opens in new tab), Diamant sought to create a fresh and up-to-date resource (opens in new tab) that could further inform and energize the next generation of menstrual activists efforts.

"Period." is filled with rich personal testimonies, details of political and organizational strategies, and Diamant's own wisdom on a variety of issues, from religious rituals surrounding menstruation to pop culture celebrating menstruation to marketing critiques of menstrual products. The powerful, raw voices of activists and everyday people are woven throughout the book, including bittersweet first (and worst) menstrual experiences, struggles with the trauma of menstrual poverty, and stories of overcoming deeply ingrained stigma and shame. Diamant knows it all and expresses it lovingly, with the keen eye of a reporter, the soul of a storyteller, and the voice of a trusted narrator. Her commitment to social justice and the dignity of all shines through.

As an outspoken advocate for menstrual equity myself, "Period. End of Sentence." has given me an opportunity to reflect on ways to rethink and strengthen the collective impact of our movement. The following are my biggest takeaways from the book.

Diamant discusses the robust legal and policy agenda underway in the United States (see 2021 policy goals here (opens in new tab)). But it is the personal stories she tells that are the lifeblood of organizing.

For example, it is the justice system that is the focus of reform. As Diamant highlights in the book, the legislatures of 13 states (opens in new tab) and several large cities like New York (opens in new tab) and Los Angeles (opens in new tab) now mandate that incarcerated people have access to sanitary products The law requires that all incarcerated people have access to sanitary napkins and sanitary napkins. Congress has mandated the same for federal prisons

. Last summer, as people across America took to the streets to protest racial injustice, I met a woman. She was menstruating at the time and was denied even toilet paper while in custody. Eventually, she was handcuffed and, with the help of her cellmate, managed to remove her saturated pad in plain view of everyone. Her story has fueled me to recalibrate my advocacy efforts to expand the coverage of laws addressing menstruation, detention, and incarceration to cover everyone in the vast system. Diamant's book fully reinforces this goal.

Period. End of sentence. (The book and film) focus on youth and education. As a result, I am motivated to reexamine the strength and scope of the law requiring access to sanitary products in schools. Especially in light of a new study (opens in new tab) showing that 1 in 10 college students were unable to afford sanitary products during this pandemic. Women of color have experienced disproportionate harm. Nearly a quarter of Latino respondents and 20% of Black respondents reported regularly enduring period poverty, and the rate was higher among first-generation college students.

However, laws addressing access to menstruation often fail to meet the needs of those most at risk. Six states (open in new tab) currently require that napkins and tampons be provided in middle schools. But what happens when schools are closed due to a pandemic or for summer vacation, as many schools experienced last year? Given the alarmingly high rates of menstrual poverty among college students, how do we pivot and ensure that campuses are not excluded from the state mandate?"(Earlier this month, Washington State (open in new tab) passed a new law expanding the provision of sanitary products to colleges and universities.) These are important considerations that must be incorporated into the next generation of policy development. Diamante's narrative supports this broader approach.

Leaders around the world are trying to make significant changes. Since Diamanté's book was published, an Irish grocery chain (opens in new tab) has begun offering free sanitary products to shoppers. Scotland (open in new tab) became the first country to mandate that sanitary products be provided free of charge to those in need earlier this year. New Zealand (opens in new tab) plans to do the same in all schools. [The Coronavirus Assistance, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020 (open in new tab) is part of the important changes that Diamant mentions. There are other federal advances: pads and tampons are among the essential items available through certain federal emergency grants (open in new tab), and the Veterans Health Administration (open in new tab) must make menstrual supplies freely available at all VA facilities.

Still, we can and need to do more. New federal legislation worth supporting includes the "Menstrual Equity in the Peace Corps Act" (opens in new tab) to ensure access for our national volunteers and the re-proposal of the "Menstrual Equity for All Act" (opens in new tab). The bills are intended to alleviate menstrual poverty for multiple populations, including Medicaid recipients, those experiencing homelessness, students in all learning environments (elementary, middle school, and college), and inmates, including those held in federal detention centers.

Diamant mentions the fight to eliminate the "tampon tax." Tampon taxes must be fought state by state (and sometimes by municipalities and counties) because that is where sales taxes are levied. Here in the U.S., 30 states (open in new tab) still do not impose sales tax on sanitary products. (Click here (opens in new tab) to see where your state stands and how you can take action.)

But countless other significant changes can be made in our own communities. We can ask them to address menstrual needs at the facilities they oversee, whether it be libraries, recreation centers, or food drives. As Diamant reminds us, part of acting locally is simply to speak up. Write an op-ed or letter to the local newspaper. Write letters to your representatives. Fight back against menstrual shaming and cyber bullying. Let's make sure everyone feels safe to speak their truth.

The louder and prouder we all are to claim these stories and connect them to our advocacy and activism, the harder it will be to ignore this issue, eradicate stigma, pass better laws, and let menstrual equity rule for all! we can move forward to ensure a world where menstrual equity reigns for all. Above. End of Sentence.

.

Comments