Consumption of trauma porn is not allyship.

"You are being ignored. I don't want to lose you today," I said to a white staff member at the mental hospital where I had been admitted for a month and a half. He had made it clear from the day I was admitted that he hated me. 'What did you say to me?' he yelled, positioning himself to block my path. I rolled my eyes and tried to walk past him. Before I had taken two steps, he slammed my head against the wall. Then he swept me off my feet with his foot, knocking me to the ground.

I started yelling at him to get away from me. He lied to his colleague that I had attacked him, ordered her to issue a "Code 100" and dispatched several other staff members to restrain me. He placed his right forearm on the back of my neck and put all of his weight on my 13-year-old. I tried to fight him off.

"I can't breathe," I managed to scream from under the pile of staff dogs helping to hold me down.

No one was listening.

Two weeks ago, I was sitting at my computer with tears streaming down my face. I was watching a video of Derek Shovin with his knees firmly planted around George Floyd's neck (opens in new tab) and fear filling Floyd's eyes. It was a moment all too familiar. The caption of the post read, "Last words: can't breathe." This video evoked unbearable memories and opened up old wounds in me.

After watching the video, I was overcome with an irresolvable frustration. Not only was I angry at being caught off guard (the video played automatically as I scrolled through it), but I was outraged that thousands of white Americans who were unwilling to help dismantle systemic racism had left George Floyd defenseless against police brutality (opens in new tab).

America has always depended on the pornography (opens in new tab) of black death and trauma.

The consumption of black pain is as American as the apple pie once brought to a lynching barbecue in the early 1900s. At that time, white mobs made up dubious accusations against black men and ultimately decided to lynch them. For weeks, the accusers advertised the "event" in local newspapers and gathered families from all over to witness (opens in new tab). While the victims were tortured for hours, participants shared meals, fellowship, children played, and ate ice cream sundaes. While the victims are tortured for hours, the children play and eat ice cream sundaes. Later, the bodies are burned, and family members take pictures next to the bodies, which are then made into postcards. Once the bodies were dismembered, participants were allowed to take home pieces of lynching flesh, bones, and rope as mementos.

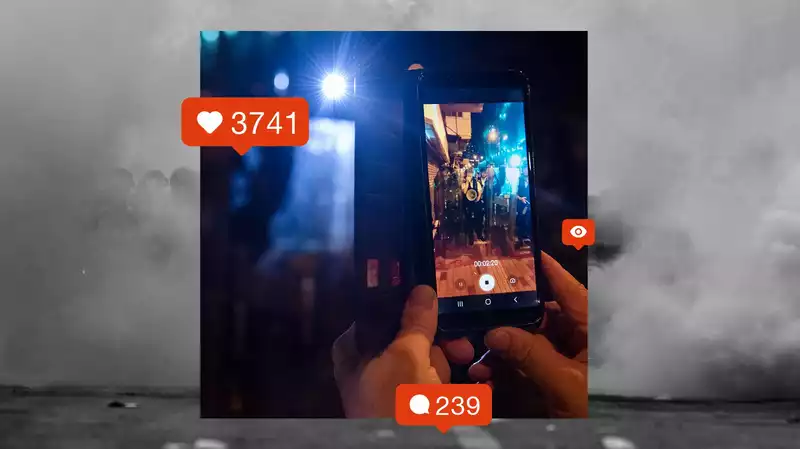

Today, however, society participates in a modern form of lynching: the sharing of trauma pornography. The methods may have changed, but the motives remain the same. The extreme discomfort you may have felt while reading the details of lynchings in the last century is similar to the discomfort many blacks feel when viral videos of us being publicly murdered are shared on the Internet. Lynchings were done to terrorize, humiliate, and inflict pain on black bodies. [17] [18] The purpose of publicly torturing black bodies, then and now, is to deter black Americans from challenging white supremacy. And re-sharing videos of blacks being murdered, "liking" and posting, you are inadvertently helping to spread that message. When was the last time you saw a video of a white person being murdered on Instagram? There have been several shootings recently, but no photos or videos of the victims at the time of their deaths are being spread. Most of the images and videos of death we see in the media and social media are of black and brown people.

As human beings, death puts us at the pinnacle of vulnerability. The deceased, regardless of skin color, is entitled to privacy, dignity, and respect in their final moments.

You may wonder: what is wrong with sharing a graphic video (opens in new tab) about the death of a black person? If the video is meant to arouse public outrage and demand justice," the viral video of George Floyd's murder led to multiple arrests that felt like justice to many. But even if cops and vigilantes are charged and convicted of killing black people, that is only half the victory. Arresting cops without dismantling the system that shaped them is like arresting guns instead of criminals. Cops and vigilantes who kill blacks are not isolated cases; they are, in fact, part of a larger, systemic problem. White supremacy is the ultimate culprit, and it gets off scot-free every time.

Perhaps, as a white ally, you breathed a sigh of relief when the officer responsible for George Floyd's death was arrested. Perhaps you thought your work here was done. Unless you pull up the roots of systemic anti-Blackness, you are merely putting a band-aid on a gunshot wound.

Sharing images of black deaths on social media will not save black lives. Instead of eradicating the murders, it normalizes them. Year after year, year after year, the blood of innocent blacks continues to be spilled, and yet the system responsible remains intact.

The fact that you have come this far is proof that you are ready to take action. Instead of posting videos on Instagram, here are eight ways you can help destabilize white supremacy in America:

Learn more about how to actively work toward racial justice.

In the future, when you come across content that includes the pain, suffering, and death of black people, please carefully consider whether you should share it.

Questions that may help you make that decision include:

"What is your intention in sharing this?"

"How can sharing this help or hurt?"

"How can sharing this contribute to a social ecological system that has this outcome for black people?"

And most importantly: "Other than sharing this content and spreading awareness, what am I going to do offline to break the vicious cycle of anti-black violence that is destroying black lives?

.

Comments