A Journey of Self-Worth in the Scars of Self-Injury

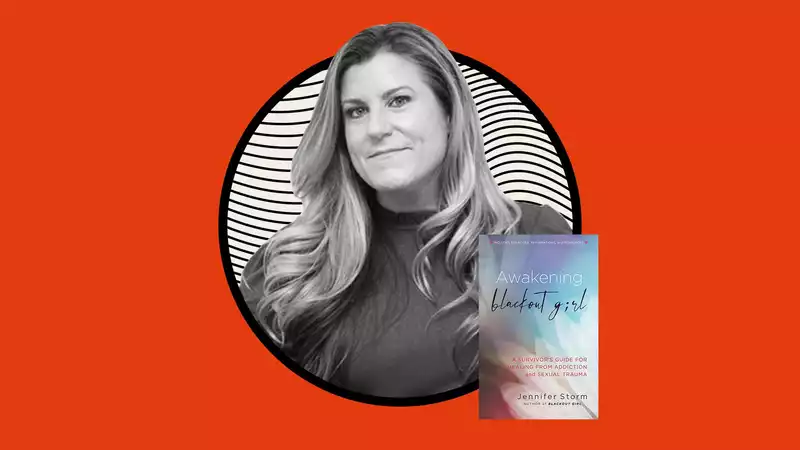

In her honest and practical guidebook, Awakening Blackout Girl (available October 6), rape survivor and award-winning victim advocate Jennifer Storm (opens in new tab) shares information, tools, and resources from over 20 years of personal and professional experience She shares and supports peers recovering from co-occurring sexual trauma and substance abuse. In this excerpt from her new book, Storm recalls the turning point that led her away from suicide and her efforts to accept her scars after years of self-harm.

My self-harm began shortly after I was raped at age 12. I was emotionally twisted and had no support or emotional outlet. My parents did not know how to deal with my trauma, and my rape only brought to the surface their own childhood trauma. None of us knew one bit about how to deal with such intense emotions in a healthy way. One night, I began to feel extreme anxiety as uncontrollable emotions welled up in my small body. Unable to bear the pain within, I tried to calm it down. I grabbed a bottle of peach schnapps from my parents' liquor cabinet, which was readily available, and rummaged through the kitchen cabinets for my mother's bottle of Valium and my grandmother's blood pressure tag. I gave myself one injection after another as I popped the pills into my mouth. When I called my mother to tell her what I was doing, her words became slurred. I hung up the phone and tried to walk to the sink to get some water, but my legs wouldn't move. Her legs collapsed and she slid to the floor between the island and the sink. The next thing I remember is the paramedics coming into the house and carrying me to the ambulance. My already blurry vision was blocked by the lights and I could see nothing. I felt a tube being inserted into my throat, a bad taste filled my mouth, and I leaned forward and vomited black charcoal. Everything went black again.

This suicide attempt landed me in the ICU. The drugs nearly killed me, but I managed to survive. When I woke up, my parents informed me that I would have to spend some time in the psychiatric ward of the hospital because I had been deemed a threat to myself. There I spent my thirteenth birthday and the following summer. To say that this was a trauma-free place would be the understatement of the century. It was as if I had been dropped into the middle of a horror movie. The floor I was on was a hospital with one long hallway with rooms on either side. My roommate was a girl about six years older than me. She had long dark hair and lay very quietly in bed. I didn't sleep a wink that first night. I was so worried because all I could hear from across the hallway was the screams of an older woman. Apparently she had been resisting treatment all day and was in four-point restraints. She had been screaming all night

If you have ever seen the movie Girl, Interrupted, you know that the floor I was on was not just for women. And it wasn't just teenagers. They were of all ages and genders. They brought everyone together without any consideration of how it would affect us. And it affected me. Over the summer I learned a lot. Older patients taught me how to lie to the doctors to get them to leave me alone. I learned how to use my tongue to keep from swallowing pills. I learned the value of different medications. Psychotropic drugs were very valuable. Unfortunately, I was only on low doses of antidepressants, which no one wanted.

One day I found my roommate showering and making cuts on her stomach with a piece of metal from a pencil eraser. She looked relaxed and calm. I screamed as my eyes focused on the blood pouring down the drain from her face. She immediately jumped up, shushed me, and begged me not to say anything. I just stared in horror and a certain amusement at the scene unfolding before me. I asked her what she was doing. She replied, "I was just sitting on the floor that day, dumbfounded. I spent a lot of time that day just sitting on the floor, stunned, thinking about what I had seen.

Months later, after I was released, I was in my own little bathroom, dragging a razor blade lightly under my arm, remembering the peaceful expression on my roommate's face as she lay face down in that shower stall. That peaceful look on her face gave me all the courage I needed to plunge the razor deeper into my own flesh. It was there that I learned about self-mutilation, or "cutting" as many people call it today. At the time, there was no official name for it. Cutting became part of my dysfunctional survival routine. It gave me a temporary emotional release when I was in pain and didn't have immediate access to drinks or drugs.

Many years later, shortly after my mother died, I experienced so much overwhelming emotional pain that I attempted to end my life again with a combination of alcohol and razors. That night I made a scar that still remains on my wrist to this day. Fortunately, that night was also my turning point. When I woke up in the hospital, I knew I didn't want to die anymore. My life was worth living, and in order to save myself, I needed to get sober and heal from my trauma.

In the beginning of my cleansing and sobriety, I had a very visible scar on my wrist that was incredibly embarrassing and filled me with shame. For a long time, these scars reminded me of the illness I had carried in my heart for so long. I felt that this scar revealed that I had tried to take my own life and that anyone who saw this scar would judge me as a madman. The only way to hide the scar was to wear long sleeves. I would roll the fabric of the sleeves over my hands and grasp them to hide the scars. That was before I wore cool sweatshirts with thumb hooks that easily hid my wrists. Those were made for runners to keep their hands warm, but they sure came in handy for me back in the day. As summer came and it began to get hotter, I had to come to terms with the fact that I couldn't always hide my scars. I used vitamin E and a list of over-the-counter products that claimed to make scars less noticeable. Although I tried everything, I soon discovered that over time, the angry raised lines would only gradually flatten out and would be impossible to erase completely. I realized that I would have to learn to live with my scars.

Part of learning to love myself was learning to love my scars. Every day, I looked down at my scars and gently traced them with my fingers. Often, I even kissed and hugged my own arms. These simple acts of kindness allowed me to physically love a part of myself that I had previously considered invisible to the world. I was able to heal myself. By allowing myself to love my scars, I removed emotional and psychological pain. I no longer feared my scars. Scars no longer represented my self-loathing. Instead, scars were part of my journey to healing, a path from my old life to my new freedom.

If you are thinking about suicide, concerned about a friend or loved one, or in need of emotional support, the Lifeline Network is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, throughout the United States at 1-800-273-8255.

Adapted from "Awakening Blackout Girl" by Jennifer Storm © 2008, 2020 by Hazelden Foundation.

.

Comments