The Big Business of Activism

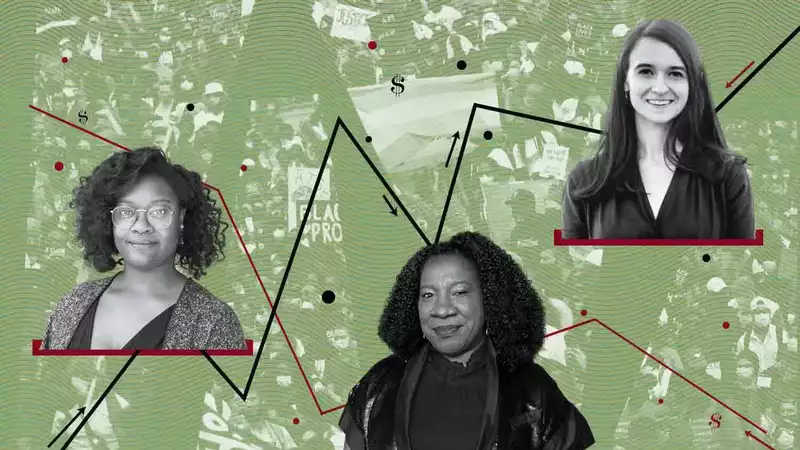

For Octavia Smith, the days following the murder of George Floyd were sad, angry, and transformative. Smith (who is gender ambivalent and uses different pronouns for her and them) is the president of the Minnesota Freedom Fund (opens in new tab). At the time of Floyd's death, the MFF had an annual budget of about $100,000 and was run by two staff members and rotating volunteers. As the protests spread, the MFF mobilized and set up $10,000 bail for arrested protesters.

However, when the staff checked the donations on Wednesday, the day after Floyd was killed, they were shocked to find that the total was $8 million. Smith describes their initial reaction, "I was just baffled. I thought, 'What is going on? I wondered how they knew [about us]." By Thursday, MFF had raised more than $20 million, thanks to tweets from Kamala Harris and other celebrities highlighting MFF's work and posting messages urging people to send money elsewhere. But the money kept coming in; by mid-June, the fund had reached nearly $35 million. Suddenly, MFF was no longer an obscure, marginally funded organization, but a well-funded nonprofit with nearly one million enthusiastic donors; MFF had little staff to spend the funds needed to pay the legally mandated bail. In fact, MFF only spent $200,000 (all it could have spent) in about two weeks and received a backlash.

Smith, who worked four to five hours a month at MFF, took time off from his full-time job. He initiated the hiring process for a new Executive Director and contracted with a strategic communications firm to manage all interview requests.

Smith is one of many activists who have emerged from a politically and socially charged culture and have become organizational architects. Over the past decade, many new groups have emerged organically after an issue, a call to action, or a bizarre spreadsheet exploded on social media. To name a few: Black Lives Matter, Women's March, #MeToo, March for Our Lives, Indivisible, etc. Existing organizations such as MFF have entered new territory. For those who lead these organizations, this transition is shocking and difficult. What happens when the social justice movement they have organized becomes, sometimes literally overnight, a highly visible powerhouse that must have staff to pay salaries, respond to donors and social media followers, and maintain 501(c)(3) tax status?

According to Rosemary Clark-Parsons, an expert on digital media and activism at the University of Pennsylvania, the rapid growth of organizations today is unprecedented. Whereas former advocacy groups spent years meeting in church basements and crafting their value statements before attempting ambitious public events, the Women's March was drafted over a weekend. Black Lives Matter went from a Facebook post to a viral hashtag and eventually became a very powerful global movement. The March for Our Lives in response to the shootings was announced online by survivors of the Parkland shooting four days after it occurred. Says Clark-Parsons: "The event comes first, the organization comes after."

Tarana Burke had been active for years, but her rise to fame was sudden: on October 15, 2017, the phrase "Me Too," which she coined as a community organizer in 2006, was reinvigorated by Alyssa Milano's #MeToo post and became a viral social media movement. Initially, she panicked. She then became the whirlwind public face of the cause as Time magazine's "Person of the Year," a guest at Michelle Williams' Golden Globe Awards, and an in-demand speaker and consultant for other advocacy groups. But around the time of Brett Kavanaugh's Supreme Court confirmation hearings, she realized that she could not achieve her goals simply by being prominent. Says she, "Celebrities in the movement don't move the needle." So she founded Me Too International, a global effort to end sexual violence, and hoped that her newfound visibility and fundraising abilities would help her envision campus initiatives at HBCUs, survivor networks, leadership training, and other projects, she hoped it would help her carry out. But even as she was about to realize this dream, she was viciously attacked online, received death threats, and had to move house. Her stardom was both a trigger and a risk.

"The hardest thing for leaders running large national organizations is that they started out as activists," says Kat Calvin, founder of Spread the Vote. They are now expected to succeed in a completely new role: running a business. 'What they want to do is campaigning, take to the streets, but it's not a job.'

When the progressive advocacy group Indivisual decided to form a national organization after a widely circulated Google document on congressional aides, Ezra Levin had to convince co-founder (and wife) Leah Greenberg that she could be effective as a co-executive director, and outside He had to hire a consultant. It was terrifying on every level," she says of the early months, when she and Levin barely slept and each lost 20 pounds. She says, "Leading rallies, staying in touch with chapters, fending off attacks from the conservative media.

Some groups have brought in more experienced leaders to ease the transition. Times Up hired Michelle Obama's former chief of staff, Tina Chen; after its first event in 2018, March for Our Lives founded the anti-gun violence nonprofit and hired longtime activist and startup whiz Alexis Confer as executive director.

Those at the top face several common challenges. One is maintaining credibility under pressure. On the other hand, they are dealing with standard issues in the start-up workplace, such as the high risk of burnout and the difficulty of creating a professional structure for and by those who may not be organizationally oriented. Amanda Harrington, vice president of communications at Time's Up, said, "When you're called to this job, it's easy to be a little anti-establishment."

But many of these new and newly energized groups have been successful in balancing growth and accountability. For Confer, this means hiring, and then supporting and mentoring, a very young staff. She estimates that two-thirds of her employees are under the age of 24, a deliberate choice to "keep the voice of youth front and center." For Burke, that means keeping the focus on black women and femmes. Black Lives Matter remained true to its origins as a grassroots, decentralized local affiliate team.

The nontraditional career path from organizing to leading a large organization may have made these leaders effective. Community mobilization, a job long neglected and performed primarily by young people and women of color, is finally being recognized for its value as an incubator for executive-level skills such as relationship building, cultural competency, and gentle persuasion. As Smith notes, this toolbox has long been dismissed as a feminized "soft skill." However, empowerment is now increasingly seen as its asset.

This empowerment of the organization and its captains has generated great excitement among donors and among the leaders themselves. For Smith, the rapid growth of MFF is mind-boggling. "Me and Octavia just imagine it, relaxing on the steps of our home," she says. "If you have the resources and privilege to do something about it, it's something else," she says.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of Marie Claire.

Click here to subscribe (opens in new tab)

.

Comments